Although, when I was first given the assignment of drawing Beavis and Butt-Head comic book I had been told by Marvel’s Executive Editor that, “… if you’re lucky, you might get two years out of it”, when the two-year mark rolled around in January of 1996, I continued to focus all of my time and energy on the project as if it were going to last forever.

Early in 1996, when I was in the middle of drawing issue 24 of what wound up being a 28-issue series, I received a phone call from Joe Orlando’s office at Mad Magazine.

Joe wanted me to “try out” for the team. If I did a great job on my sample page, I might become one of “the usual gang of idiots”.

Instead, when all was said and done, I was just an idiot.

Mad Magazine and Mad Comics before that had been a big deal to me when I was a kid. I had always liked to draw and EC Comics and Mad Magazine, in particular, had made a huge impression on me.

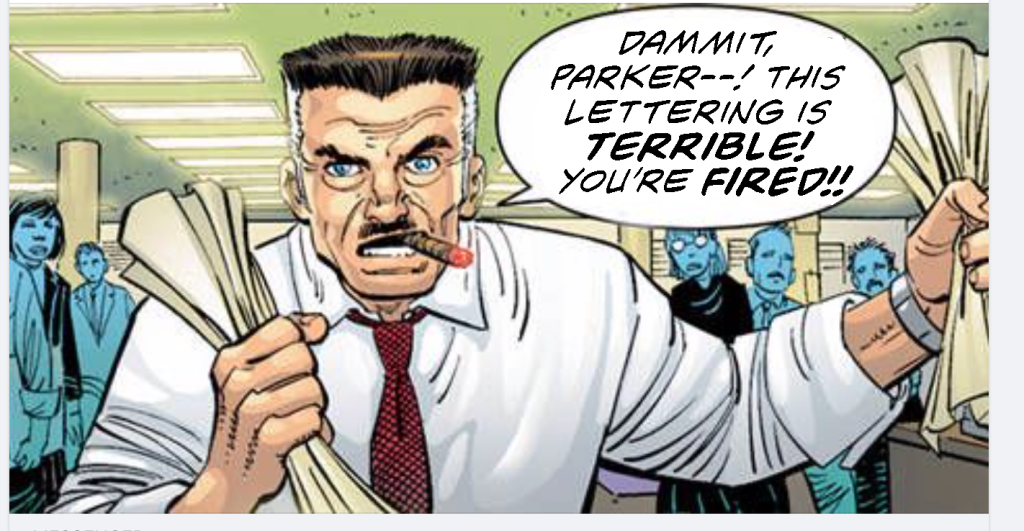

Although it was never my ambition to be a cartoonist for Mad, when I was working for Marvel, the current editor-in-chief, Tom DeFalco and Jim Shooter, the one before him had both told me, “You should be working for Mad.”

I found their comments somewhat bewildering as in, “What—you don’t want me working here at Marvel?” After all, before Beavis and Butt-Head I was writing and drawing a cartoon strip for about a year which featured an exaggerated cartoon version of Tom-–along with cartoon versions of other Marvel employees from Stan Lee to assistant editors and production people.

I thought my star was rising.

What I failed to realize– or refused to accept –was that while Marvel had indeed made a few half-hearted attempts at doing “humor”, Marvel was, at its core, a Superhero company. And I was not a superhero artist.

My work fell into the “Weird Humor” category,

So when Mad called me and invited me to try-out for the team, especially with Beavis and Butt-Head winding down, I should have jumped at the chance and taken this opportunity more seriously.

After all, becoming one of the artists at Mad was a lifetime appointment, like getting a seat on the Supreme Court!

It didn’t really help that a few months earlier, at a comics event, I had been introduced to Sam Viviano, the Art Director of Mad, and although he seemed to know who I was, when he said, “…you’re familiar with MY work, aren’t you…?” having been raised to tell the Truth, I responded, “No….not really…”

A few days after the call, I took the subway up to Mad to pick up the Try-Out page and was pleasantly surprised by the warm and friendly greeting I received from Mr. Orlando’s beautiful secretary.

True, being the artist of a very popular comic book for the last couple of years had given me an inflated sense of my own importance, at least around comics fans, still, I was not accustomed to being treated like I was a celebrity by someone’s secretary.

On the subway back to my apartment, I looked the page over and was not inspired –and laid it down next to my drawing board for a day or two hoping inspiration would strike.

Then went back to work on Beavis and Butt-Head.

I have never been especially good at juggling multiple projects and prefer to focus all my attention on one thing at a time.

When I still hadn’t touched the Try-Out page two weeks later, Joe’s office called again.

So I held my breath and did it.

I did not give Mad’s Try-Out page the attention that I should have. And my “Try-Out page” was a testament to that in black and white.

On the way to Joe Orlando’s office to show him my page, I happened to pass Paul Levitz, DC’s publisher, in the hallway. Without knowing the reason for my visit he said, “You should be working for Mad”, as we passed each other.

Once again, I received an “insider’s’ greeting from Mr. Orlando’s secretary. I shook hands with Joe and I handed over my try-out page.

He didn’t say a word.

He didn’t have to.

His face told me everything I needed to know. He seemed even more disappointed in my effort than I was.

He then quickly proceeded to show me the samples of another artist they were considering, who had drawn the main character, the Democratic strategist, James Carville dozens of times–until he “owned” the character.

Perhaps out of embarrassment and rather than simply showing me to the elevator, he walked me down the hall and introduced me to John Ficarra, the Editor of Mad Magazine and his associate, Nick Meglin.

Mr. Ficarra leafed through a few of my Beavis and Butt-Head pages which I had brought along, convinced that they better represented what I was capable of. Interspersed were smaller illustrations from a humor book I had illustrated a few years earlier. The latter drawings featured my original characters and highlighted my “fine line” quality approach to drawing.

After a minute or two, Mr. Ficarra said, “I see that you know how to use black to good advantage…”

“Did you used to work for Disney?“, Mr. Meglin asked.

Somewhat puzzled I asked, “No, why…?

Pointing to a figure that was a hybrid of realistic and “cartoony” he quipped, “Because all your characters have three fingers.”

I didn’t laugh, though now I wish I had.

Even if he was being sarcastic, it would have been the “nice” thing to do.

The truth is, I always assume people are being straight with me and I take everything people say literally. And I didn’t appreciate my artwork being made the butt of a joke.

Months later, after Beavis and Butt-head was canceled, along with all the other licensed properties, and I was completely without work, I found myself up at DC, illustrating some stories for the Big Book Series. I stopped by Joe Orlando’s office to say hello and approached his secretary. Rather than the warm and friendly greeting I was expecting, fully aware that I hadn’t “made the team” she treated me like I was a total stranger.

Such was the plight of one who was called and not chosen.

When I was growing up, there was a boy in my neighborhood who was several years older than I was–and he was fond of bullying me. One morning, I was alone shooting baskets in our driveway when he approached me from the street.

When I was growing up, there was a boy in my neighborhood who was several years older than I was–and he was fond of bullying me. One morning, I was alone shooting baskets in our driveway when he approached me from the street.